Remember the “Jamestown Rosetta Stone” that I blogged about last summer?

Well it looks like curators at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C., have started to decipher the text etched into this slate. The tablet has on one side inscribed: “A Minon of the Finest Sorte“ and a more cryptic message: “EL NEV FSH HTLBMS 508,” among drawings of people and single letters. The article does not mention anything about those cryptic phrases, so my guess is that they are still scratching their heads.

I find this to be fascinating. Although U.S. history is relatively a young compared to other countries history, there is still a lot to be discovered.

Full source: NatGeo

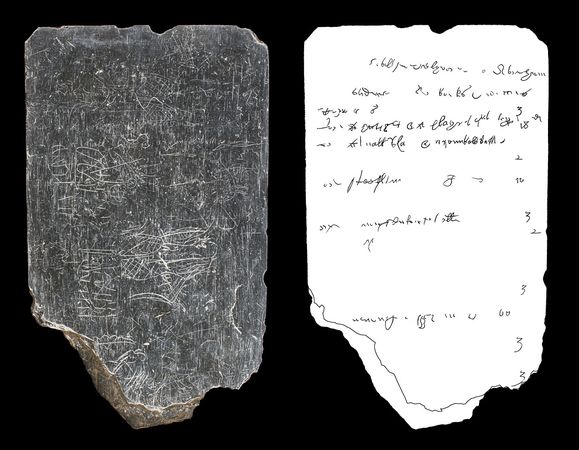

A conservator digitally isolated inscriptions (right) on the 17th-century Jamestown tablet (left). Photograph: Preservation Virginia

Paula Neely

for National Geographic magazine

January 13, 2010

With the help of enhanced imagery and an expert in Elizabethan script, archaeologists are beginning to unravel the meaning of mysterious text and images etched into a rare 400-year-old slate tablet discovered this past summer at Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in America.

Digitally enhanced images of the slate are helping to isolate inscriptions and illuminate fine details on the slate—the first with extensive inscriptions discovered at any early American colonial site, said William Kelso, director of research and interpretation at the 17th-century Historic Jamestowne site (Jamestown map).

(Explore an interactive guide to colonial Jamestown.)

The enhancements have helped researchers identify a 16th-century writing style used on the slate and discern new symbols, researchers announced last week. The characters may be from an obscure Algonquian Indian alphabet created by an English scientist to help explorers pronounce the language spoken by the Virginia Indians.

“Just like finding the Rosetta Stone led to a better understanding of the Egyptians, this tablet is beginning to add significantly to our understanding of the earliest years at Jamestown,” Kelso said. It conveys messages about literacy, art, symbols and signs personally communicated by the colonists who used it, he explained.

“What other single artifact has been found that has so much to tell?”

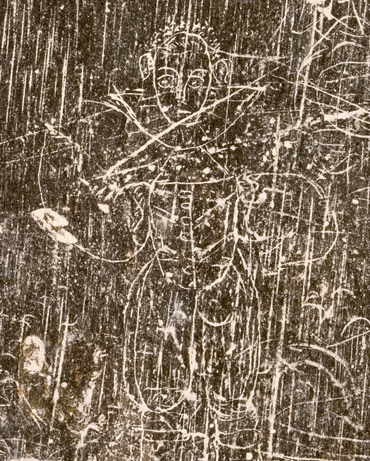

Both sides of the scratched and worn 5-by-8 inch (13-by-20 centimeter) tablet are covered with words, symbols, numbers, and drawings of people, plants, and birds that its owner or other users likely encountered in the New World.

There are differences in the style of handwriting, which may mean that more than one person used the tablet as a sketch pad and possibly for writing rough drafts of documents, Kelso noted.

Enhanced Images

To help researchers decipher the inscriptions, curators at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum Conservation Institute recently produced enhanced images of the slate through a process known as reflectance transformation imaging.

Hundreds of high-resolution digital images were taken of the tablet using multiple angled lights to exaggerate the appearance of grooves in the slate’s surface—like watching the sun rise and set on an object.

The images on the slate are difficult to see with the naked eye, because they are the same dark gray color as the slate and they overlap.

Colonists would have written on it with a pencil made of slate that left white marks. The marks could be wiped off, but fortunately for archaeologists today, the pencil had a sharp point that also left scratches on the tablet that couldn’t be erased completely. As a result, there are layers upon layers of inscriptions.

Elizabethan Script Analysis

Based on an initial examination of images, Heather Wolfe, curator of manuscripts and an expert in Elizabethan script at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., thinks that much of the cursive writing on the slate appears to be written in secretary hand, the main form of cursive handwriting taught in England during the early 16th and 17th centuries.

“Many of the letter forms are different from the forms used today. You need special training to understand them,” Wolfe said.

So far, the words “Abraham” and “book” appear to be visible, and she has been able to identify some individual letters. She hopes to be able to decipher more of the text using the images taken by the Smithsonian that provide finer details. Unfortunately only a portion of the text survived; parts of letters and some words are missing.

Wolfe explained that the practice of using erasable slates for drafting music and teaching the alphabet and spelling goes back to the 16th and 17th centuries, but they were so fragile, they usually broke.

Finding a largely intact slate like this one is “very rare,” Wolfe said. “The slate provides a unique window into a practice that we’ve known about, but that we haven’t seen before.”

Algonquian Pronunciation Symbols

Historic Jamestowne’s Kelso said the enhanced images also revealed two symbols that are similar to characters in a phonetic Algonquian alphabet invented in 1585 by Thomas Hariot.

The English scientist participated in the expedition to establish an ill-fated colony on Roanoke Island—in what is now North Carolina—for his patron, Sir Walter Raleigh, that same year. (Related: “Search for America’s ‘Lost Colony’ Gets New Boost.”)

It wasn’t until after archaeologists had discovered the slate that Kelso was made aware of the 36-character alphabet by a researcher attending one of Kelso’s lectures. The alphabet survives as a manuscript in the library of the Westminster School in London.

Kelso said there are also documented references to a dictionary of the Algonquian language, which some scholars think Hariot developed, since he had had the opportunity to learn the language from Native Americans who returned to England with the explorers. Fire destroyed the dictionary in 1666, and there are no surviving copies, he said.

“When I found out about it,” Kelso said, “the probability that the European explorers likely showed up at Jamestown with bilingual dictionaries, ready to communicate with the Indians, made perfect sense,” he said.

Other details revealed through the enhanced images will help researchers determine the sequence of the inscriptions.

“In a way, it’s a mini-archaeology site. If one groove cuts across another groove, you can tell which one was the most recent,” Kelso said.

Smithsonian curators also used x-ray fluorescence to identify the chemical composition of the slate and create a geological profile. The results will be compared to slate samples from different locations in Europe to learn the origin of the slate.

Found in John Smith’s Well

Archaeologists discovered the slate in the center of James Fort in a well most likely built in 1609 under the direction of Capt. John Smith, a founding leader of Jamestown, which was established in 1607.

When the water in the well went bad, colonists used the well as a trash pit. They discarded the tablet and thousands of other artifacts during the winter of 1609-10, called the Starving Time.

Near the slate, archaeologists found butchered bones from horses and dogs, which may date to the same period, when the fort was under siege and colonists resorted to eating their domestic animals. Only about 60 of 200 people survived the winter.

Archaeologists reached the bottom of the 14-foot-deep (4.2-meter-deep) barrel-lined well in December. They are currently analyzing, conserving and restoring the rest of the enormous and unprecedented collection of artifacts. The analysis is expected to lead to a better understanding of the colony’s difficult early years.

Whose Slate Was It?

Kelso speculates that the slate belonged to William Strachey, the first secretary of the Jamestown colony.

Strachey had legal training, so he would have known how to write using secretary hand. He was also among the 140 castaways from the Sea Venture, an English ship that sailed for Jamestown in 1609 with supplies and more settlers to reinforce the colony.

The ship was wrecked in a storm and its passengers were stranded in Bermuda for ten months. After building two new ships, they arrived at Jamestown in the spring of 1610, in time to help those who had survived the winter.

Previously identified drawings on the slate may indicate that the owner traveled through Bermuda. These include a palmetto tree and possibly a cahow—a rare seabird that nests only in Bermuda.

Drawings of rampant lions, used in the English coat of arms during the 1603-25 reign of King James I, were also identified earlier and suggest that the owner was involved with government and armorial drawings—evidence that Kelso believes also may point to Strachey.

In the months to come, the Jamestown slate will continue to undergo a variety of nondestructive analytical tests.

“We have only begun to bleed the secrets out of this extraordinary object,” Kelso said.